The early years of computer animation

An excerpt from an autobiography by Micheal Parks

Prologue

After I graduated from college in 1976 with a degree in fine arts, I applied and was accepted to the Johnson Atelier Sculpture Institute in Princeton, New Jersey, for training in bronze sculpture casting and mold-making. After sufficient education in this field I returned to my home state to build and operate a small sculpture foundry. The foundry proved to be unsustainable, primarily because of its remote rural location on the shore of Lake Bistineau in northwest Louisiana. After a few years of struggle to make the venture work I decided to change channels. I sold all the equipment and launched into residential home construction by designing and building my first house for my wife and newborn son.

A few years later, I designed and built a second house, this one on spec, just in time for the oil market to collapse in 1986. The price of crude oil dropped to below $10 a barrel, causing a massive recession in Louisiana and leaving me with a spec house I could not sell except at a loss. This turn of events made it difficult and foolish to continue as a start-up home builder. I decided to re-educate myself in order to qualify for a new career and enrolled in DeVry University at Las Colinas in Dallas, Texas, to study electronics engineering technology.

Introduction to Computer Graphics

Toward the end of my first semester at DeVry, one of the instructors suggested that we visit a gathering at the Dallas Convention Center that could give us some insight into the latest technology in computing and electronics. The convention was the 1986 annual meeting of the Association for Computing Machinery’s Special Interest Group on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, otherwise known as ACM SIGGRAPH. We were offered free passes, so I went to the convention center to check it out.

The SIGGRAPH convention was huge. I was overwhelmed by the size of what was going on there. Thousands of people had gathered from all over the world for a three-day conference dealing with the latest technology and discoveries, primarily in the field of computer graphics. There was a vast convention hall showroom filled with all the latest advances in computer hardware and software applications designed to accommodate this rapidly emerging field. When I walked onto the showroom floor, the first booth I saw was for a company called Wavefront Technologies. Wavefront had developed 3D animation software and was featuring incredible computer-generated 3D animations playing on several large color monitors at the front of their booth. When I observed what was going on in those monitors, I had a eureka experience—the realization that this is what I wanted to do. The new technological domain of 3D computer animation was the perfect combination of painting, sculpture, architecture, electronics, computers, and pretty much everything I had ventured into up until now. I knew right then and there that was what I was going to aim for. Somehow, I was going to get involved with this, no matter what it took.

For the next

few hours I was ecstatic, looking at every booth on the showroom floor, taking

in as much as I could about computer graphics and anything related to it. I was

so pleased that I had finally found something I could visualize getting a job

doing. Of course, I first had to find a way in, but that seemed like a small

detail. I decided I was going to quit Devry and somehow find a way to enter

this emerging field of computer graphics

I spent some time researching schools that taught various aspects of computer graphics. Most educational opportunities were in the software development side of things; not many places taught the artistic use of this brand-new field. The center of the academic work in computer graphics at that time was in Salt Lake City at the University of Utah. Art Center in Pasadena, California, had a program in graphic arts that advertised some involvement in artistic computer graphics. There was also a place in San Francisco called the Computer Arts Institute that offered courses in some of the various new computer animation and graphics software tools. I decided that the first thing to do would be to check out these schools and see if I could get into a program that would teach me what I needed to get an entry-level job. If I could just get a seat at a computer running one of the new CGI animation programs, I would be dedicated to learning as fast as possible because my future depended on proving to myself and my family that I could do whatever I wanted if I put my mind to it.

My mission was fixed in my mind and without much delay I carefully packed the bed of my little Toyota diesel pickup truck with some clothes, camping equipment, a bicycle, and a few carpentry tools, just in case. When the day came for me to leave Louisiana and head west, I was overwhelmed with fear and doubt about what I was about to do. It was a strange experience, full of apprehension and anxiety, yet somehow exciting as I pulled away in my loaded pickup, not knowing where I was going or what I was going to do when I got there, but vowing I would not return unless I had a job.

A couple of days later I was heading west toward New Mexico after spending some time in Dallas dealing with a minor repair on my truck. I had a small tape recorder with me and narrated parts of my trip for my son. I could envision him being tucked into bed listening to my recordings, imagining he was traveling with me as I described the cattle yards and grasslands that made up the vast west Texas plains. At night, I stayed at empty campgrounds, sleeping on the ground, contemplating the suitability of what I was doing. For this journey, I decided to let intuition be my method of navigation as much as possible. Driving through Texas this was easy because, if you’re heading west, there are not too many choices – only miles and miles of straight highway occasionally passing through desolate towns, devoid of any place to even get a meal except for the occasional Dairy Queen or A&W.

When I got to New Mexico, I decided to head up toward Santa Fe. At Santa Fe I had to make a choice—go north toward Salt Lake or head west toward California. When I arrived in the Santa Fe area, I headed to the Shidoni Sculpture Foundry near Tesuque. I had some friends who worked there and they allowed me to camp that night in the sculpture garden on the grounds at the foundry. In the morning, I packed up my camping gear, got in my truck and started driving back into Santa Fe, still undecided which way to go. My intuition was not giving me any clear signals so I drove aimlessly around Santa Fe for an hour or so trying to make up my mind which highway to take. I was at a crossroads, not able to decide. Somewhere on the outskirts of Santa Fe I passed by an old Spanish-style house with a big sign on the front that read, “Sister Rosa – Palm Reader.” I didn’t pay much attention to it, other than thinking it looked like an interesting sign on the shabby old house. I drove a few more miles in the midday sun and the image of the Sister Rosa sign stayed in my mind. I came to a red light and had a strong intuitive impulse to go back and check out Sister Rosa. The light changed to green and instantaneously I made a U-turn and headed back to see if the palm reader was open for business.

I had never been to a palm reader before, believing that they were con artists, or at best, entertainers. I parked my truck on the street, hesitant about entering, but after a few minutes I decided to go on in. I stepped onto a small porch and knocked on the door. A woman’s voice came out of a cheap little intercom speaker next to the door and asked if she could help me. I replied that I was wondering about getting my palm read and the voice responded saying that she was with someone at the moment but would be available in about twenty minutes and I could wait outside. For some reason this intrigued me, so I got back in my truck across the street and waited in the sweltering summer heat. After a while, a woman came out of the house and got into her car to leave. Figuring Sister Rosa would now be ready to see me, I walked back onto the porch and knocked on the door.

A short little native Hispanic woman opened the door. She was old and bent over with a pleasing smile that invited me to come inside. I was led into a little room next to a small vestibule that was filled with candles and religious artifacts. The candles were all lit and provided the only illumination in the room other than a few traces of sunlight that made their way in through cracks in the window blinds. I stepped into an odd little gallery, filled and embellished with objects and effects that were seemingly part Gypsy, part Catholic. It was a stark contrast to the asphalt highway on the other side of the door.

Sister Rosa asked me to take a seat in a chair opposite her. There was a small wooden table between us. As she asked what see could do for me, I noticed a distinct whitish glow radiating around the edges of her head and shoulders. I had heard and read about auras in the past, and I believed that I had seen faint instances of such phenomena before, but the strength and vibrancy of this woman’s remarkable white aura suddenly had my undivided attention.

I told Sister Rosa that I had never had my palm read before and that I was here in Santa Fe trying to decide which way to go. I told her I had seen her sign as I was driving down the road and decided to turn back to satisfy my curiosity. She listened with compassionate eyes, and then asked me to show her my hands. She bent over the table looking carefully at my turned-up palms and after a few seconds she shook her head and simply said, “Oh my.” For the next ten- or fifteen-minutes Sister Rosa told me things that had happened in my life that were so accurate that I was completely shocked. There was absolutely no way she could have known about some of the experiences I had in my past and yet she was speaking about them with certainty, including the year they had happened, as she looked at the lines on my hands. I was so blown away by this that I had to stop her and come clean with exactly why I was there. I proceeded to tell her what had happened to me over the last few years: my failure with my homebuilding ventures, my need to find a new career, and the fact that I was headed west to get a job. I broke down and opened up my heart to Sister Rosa and told her some of the difficult details of my life that had been troubling me. I did not know this woman and I would probably never see her again, yet she had gained my trust with the purity and truth of what she had said to me. I told her that I had been driving around Santa Fe trying to make a decision whether I should head north toward the University of Utah, or west to California.

Sister Rosa listened intently until I finished my story. She was kindhearted and I believe deeply concerned about my well-being as she told me that she had an exceptionally strong feeling that I should get in my car and without any delay “head west.” She was very emphatic about this and she told me she would light a large candle for me and pray for my success. She then gave me a small amulet tied to a string. It was about the size of a postage stamp and was made out of brown felt with a small piece of white cloth sewn on that had a protection prayer written on it. Sister Rosa told me to keep this with me at all times and to wear it around my neck as I was forging ahead on my adventure. She lit a large candle and she wished me well as I left the little room, full of resolve to drive west into the desert toward Los Angeles. Before I got in my truck, I put the string around my neck and tucked the little brown protection charm under my shirt. I was on my way.

New Geography

In a couple of days, I descended into an ocean of smog that was Los Angeles in the mid-1980s. My little Toyota diesel pickup truck could only go about 55 mph, loaded down with all my stuff. In no time, I found myself in heavy traffic with cars honking at me and people flipping me off because, apparently, I wasn’t driving fast enough on the freeway. I had the accelerator pressed to the floor as I was passed by a flood of aggressive, stressed-out Californians who did not take kindly to a slow vehicle with Louisiana license plates. It was actually quite frightening. I was trying to navigate to Pasadena during rush hour at a time when road-rage freeway shootings in Los Angeles were making national news. Somehow, I was able to find my way to the downtown area of Pasadena, grateful to be alive. I found a cheap motel on one of the main streets and checked in to spend the night in preparation to visit the Art Center College of Design in the morning. The smog was so thick that the buildings across the street looked like they were in a light fog. My eyes watered and stung from the thick, toxic air. This was my first impression of Los Angeles and I didn’t like it one bit.

The next morning, I found the Art Center and met an admissions counselor who looked at my portfolio and listened to my story about wanting to get involved with computer graphics. It turned out that Art Center did not really have any kind of computer graphics department at the time—only a graphic arts program that had one computer system used for print layout, which did not really interest me. The counselor recommended that I apply for admission to their transportation design program because of my experience with sculpture. It was an intriguing proposal, but not at all in line with my intentions for coming out west. I decided to continue my journey and head north toward San Francisco to check out the Computer Arts Institute.

Heading west from Pasadena I made my way into Hollywood, on to Sunset Boulevard and kept driving toward the ocean. I was done with L.A. and wanted to get out of there as fast as I could. Sunset Boulevard ends at the Pacific Coast Highway, so when I got to the ocean, I took a right turn and headed north toward Malibu. The Pacific Ocean was a welcome sight. After driving for days through the west Texas range, the hot southwest deserts, and then descending into the intense smog of Los Angeles for the first time, seeing the vast ocean alongside the road into Malibu and breathing the cool clean salty air was a great relief. I drove north for a couple of hours as the sun set over the Pacific.

It was completely dark when I drove into Santa Barbara. A friend had moved here from Shreveport a couple of years earlier and I called him from a restaurant where I stopped to eat dinner. Fortunately, he was home, only a short distance away, and he came down to meet me. We had a couple of beers as I told him about my adventure. He invited me to stay at his place for a few days to recuperate from the last week of travel so I gladly accepted. I camped out on a floor that night in a tiny living room and slept very well. In the morning, I woke up to a beautiful day in Santa Barbara.

After eating breakfast, I decided to unload my bike and take a ride around town. Already I could tell I liked this place, with the clean crisp air and perfect temperature. I was staying a couple of blocks away from upper State Street, which I was told was the main street in Santa Barbara, so I started coasting downhill toward the ocean to check out the morning in town. After a few blocks, I was riding down a bike lane on lower State Street taking in the sights and atmosphere of one of the most beautiful settlements I had ever seen. Tall palm trees lined either side of street alongside unique Spanish-style architecture with red clay tile roofs and cream-colored stucco and terra cotta storefronts. The city was just waking up and the smell of coffee and fresh pastry was mixing with the cool clean smell of orange blossom and jasmine. I was in awe. The contrast between the previous day in Los Angeles and this place was like day and night. This was a very different kind of city than any in Louisiana or Texas, and I felt I had discovered one of the first clues I had set out to find. As I was riding my bike down State Street, something inside told me to stay in Santa Barbara. Intuitively I felt like I did not need to go any further; that what I was looking for was going to be here. It did not take me long to get a newspaper and start looking for a place to rent. Santa Barbara was going to be my base of operations for a while to work on getting started in computer graphics. I didn’t have a clue how this was going to occur but I knew I had to stop here and see what happened.

It only took me a few days to find a cottage in the Santa Barbara foothills and move in. I was lucky to find a perfect little place next door to a pottery studio run by a well-known local artist, Oscar Bucher, who was also my landlord. There were plenty of fresh oranges and ripe avocados growing right outside the door and I felt like I had just rented a cottage in paradise. I bought a few pieces of modest furniture and within a week, I was completely moved in as a new resident of Santa Barbara, California.

This was before cell phones, so I had a landline telephone installed, which came with a local phone book. I immediately looked up “computer graphics” in the yellow pages. To my complete amazement one of the few listings shown was Wavefront Technologies—the same Wavefront Technologies whose booth I’d seen at the SIGGRAPH convention in Dallas the previous year. I could not believe the coincidence. It was as if the universe was now working in my favor. I was suddenly conscious of the small brown amulet that Sister Rosa had given me hanging around my neck on a piece of string. I had been wearing it since I drove away from Santa Fe. I wrote down the address of Wavefront, as well as another listing I found, and headed into town with my resumé and portfolio. I was on a mission.

Wavefront was in a new commercial business complex not far from where I lived. I walked into the lobby and immediately understood that this was a place where high-tech programing and business development were done. I did not get the feeling that there was going to be an opportunity here for someone interested in learning how to use computer animation software for artistic endeavors. The receptionist asked if she could help me and I really did not know how to respond. I didn’t know anyone and it seemed silly to ask if there were any jobs available that would require learning how to use their product. I took a product brochure from the reception desk and told her I was interested in checking out Wavefront’s software, then walked out wondering what kind of background it must take to get involved with a company like that. It seemed pretty certain to be a background I didn’t have.

The next place on my list from the phone book was a business called Gaskell Enterprises. There was no indication of what kind of business this was, but it was listed under “computer graphics” so it was worth checking out. I found the place in an older commercial business center that was not nearly as slick as where I had just been. I went in and introduced myself to a tall lanky man named Derrick. I explained that I had just moved to Santa Barbara from Louisiana and that my mission was to get involved with the emerging field of computer graphics. Derrick was intrigued by my story and explained that his business had a license to sell two different software and hardware computer graphics products. One was a computer-aided design product from a new company called AutoCAD and the other was a computer animation software and hardware combination product called Cubicomp Picturemaker. I had never heard of either one, but they both seemed interesting.

After looking at my portfolio of paintings and sculpture work, Derrick explained that the AutoCAD license was his main product line and his specialty. AutoCAD was a recently released two-dimensional, computer-aided drafting program used by architects and engineers and he was involved with selling this product throughout Southern California. The other license for rights to sell Cubicomp computer animation systems had been handled by a partner who had recently moved away. Derrick did not know much about Cubicomp, other than it was one of the lower-cost solutions for 3D computer modeling, rendering and animation. There was one fully operational system in his office, but he did not know how to use it. Derrick made me an offer. He said that if I could spend time at his office and learn how to use the Cubicomp software, I could help him sell these systems to prospective clients by showing them how to use it. He would not be able to pay me until I had demonstrated that I could use the product and generate sales. I was completely ecstatic with this proposition. I had been prepared to come to California and spend precious time and money paying someone to teach me how to use computer animation software, and here I was being giving an opportunity to learn a system for free – all I had to do was show up. I think Derrick was quite amused at how happy I was to hear his offer. It was almost unbelievable for me. I had only been in this new environment for a few days and I had landed an opportunity to do exactly what I had set out to do. I didn’t have a paying job yet, but I knew that would come. All I had to do was learn how to use this Cubicomp. I could not help but think that whatever magical blessing Sister Rosa had bestowed, it was working. I showed up the very next day, ready to dig in.

Computer Animation 101

For the next couple of months, I spent almost every day at Derrick’s office, carefully reading the Cubicomp manual and learning the basic aspects of the software. It was a fairly complex system and a lot of the details concerned concepts and procedures that were completely new to me. Of course, there was no internet or online help in 1987. I had several large technical manuals to work with and that was it. I learned by trial and error, but I was fascinated. I would sit and work at the computer for hours with no concept of how much time had passed.

Eventually I got to a point where I could create simple 3D geometric models and do minimal animation in the computer. One day Derrick came into the room and said that he had landed a potential client who wanted an animation of a mechanical device he had invented. The goal was to provide a 3D model of this device and animate how it worked, then transfer the animation to video tape so the client could use the video to show his prospective clients. The project was not very complicated, and I was able to build the model in the computer and animate the basic components, but I had no idea how to get the animation out of the computer and onto videotape. Fortunately, Derrick’s previous business associate, Tom Ravey, was coming to Southern California to visit and arrangements were made for me to meet him to see if he could help us solve this problem. Tom had moved to Eugene, Oregon, from Santa Barbara a year or two earlier to start a computer animation production studio called Digital Artworks. I was very interested to meet him, not only because he might be able to help solve the video problem, but because he had started one of the first computer animation studios on the West Coast using Cubicomp software.

Tom was on his way to the annual SIGGRAPH Conference that was being held that year in Anaheim, outside of Los Angeles. He stopped by the office to review the work I had done with the Cubicomp. He was impressed by the fact that I had learned the basics of the system by myself. Tom invited me to ride down to Anaheim with him and during the trip we talked constantly about computer animation, the arts, and all kinds of interesting subjects. I told him my story about living in Louisiana and leaving to come west in order to find a new career. Tom was intrigued by my background with the sculpture foundry and home building, as well as my portfolio of artwork. He suggested that I travel up to Oregon and bring the animation file I had created so that his animators could load the file into their system and output it to video. The process of getting the animation from the computer to videotape required special equipment and expensive recorders that we did not have access to in Santa Barbara. It was a generous offer and I jumped at the chance to learn from spending a couple of days with computer animation artists who were experts at using Cubicomp.

Within a week, I went to Oregon and spent a few days with Tom’s animation crew at Digital Artworks. I was still not getting paid for any of the work I was doing for Derrick, nor did I get any money for this trip, but I really did not mind because I looked at all of this experience as an investment in my education. I learned firsthand what kind of professional work was being done with Cubicomp at the time and I got answers to all kinds of technical questions about how to use the software. I returned to Santa Barbara after a week with a videotape of the mechanical animation and Derrick was able to deliver the animation to his client. The completion of this first project was a success. The biggest benefit however occurred a few days afterwards, when I got a call from Tom and he offered me a job. Derrick was pleased that the opportunity he provided had worked out for me by getting the offer to relocate to Oregon to pursue a career as a computer animator.

The crew I’d met at Digital Artworks seemed to like me and had all agreed that I could be a potential member of their team if I was able to learn more about how to use the Cubicomp competently. Tom’s offer was based on me moving to Oregon and working for a month to see if I would be able to learn what was necessary in order for me to be paid full-time as a computer animator. I would not be paid for the first month – it would be a trial period to make sure I fit in and could absorb what I needed to know in order for the company to justify taking me on as a full-time employee. I would be responsible for the move and finding a place to live, but the upside would be a seat at a computer graphics workstation and a free education. Even though I would have to spend my own money to move and live in a new town for a while, this would be a much less expensive option than paying to learn Cubicomp on my own without any mentors. Of course, I said yes. It was a tremendous opportunity and if I succeeded in getting a paying job in a new career, my mission would be accomplished.

The morning I pulled out of Santa Barbara I was about 10 miles north, driving along the Pacific Coast Highway, when rain drops began hitting the hood of my truck. It struck me that the entire time I had been in California there had been no rain. On the day I left Santa Barbara, as I drove north, the rain continued all the way to Oregon. It rained in Eugene for the next thirty days, nonstop.

Virtual Reality

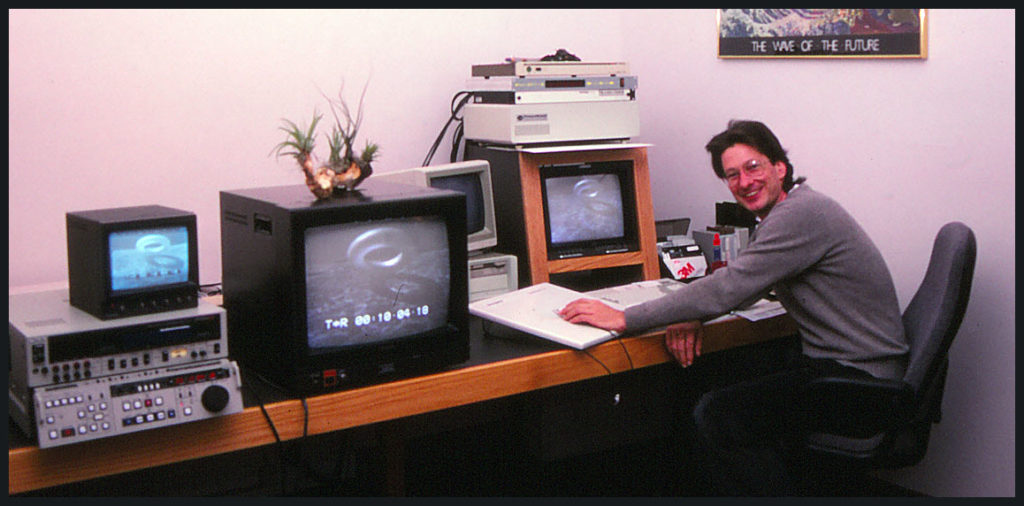

I found an apartment in Eugene without delay and within a few days started working with my mentors at Digital Artworks. Four talented animators worked there and were very gracious to me as a newcomer. Paula Conn, Erik Johnson, David Lang, and Carl Johnson were probably the most experienced Cubicomp operators that existed at the time. I was extremely fortunate to find myself sharing an office with them and having the opportunity to learn hands-on about all the tricks and techniques needed to successfully navigate the software.

For any computer geeks reading this, Cubicomp Picturemaker was one of the first 3D computer graphics systems available on a PC. There were other 3D animation software systems at the time, notably Wavefront and Alias, which ran on a Silicon Graphics Iris workstation using a UNIX operating system. The SGI Iris had a whopping 8-MHz processor (this was fast at the time – an iPhone processor is over 1000 times faster and today’s average desktop is over 3000 times faster!) with up to 2MB of memory. These systems, hardware and software included, were very expensive. When the Cubicomp Picturemaker came out, it ran on a PC, which was typically an IBM AT or a Compaq with an Intel 80386 microprocessor, 8MB of RAM and a 40MB hard drive. The PCs were much less expensive than the SGI systems, but even with this savings a complete Cubicomp workstation with a broadcast quality video recording system could cost $60,000-$70,000.

The first month was challenging and exciting as I mostly watched how the other animators produced their projects. I was given small simple assignments to figure out at first and this usually led to a multitude of questions that enabled me to take on more complex tasks. One of the animators, Carl Johnson, had taken me under his wing and was my key mentor in learning the software. I learned quickly and spent nearly all of my daylight hours in the office in front of the computer monitors. In only a few weeks I achieved the goal that I originated when I left Louisiana: a full-time job with a decent salary.

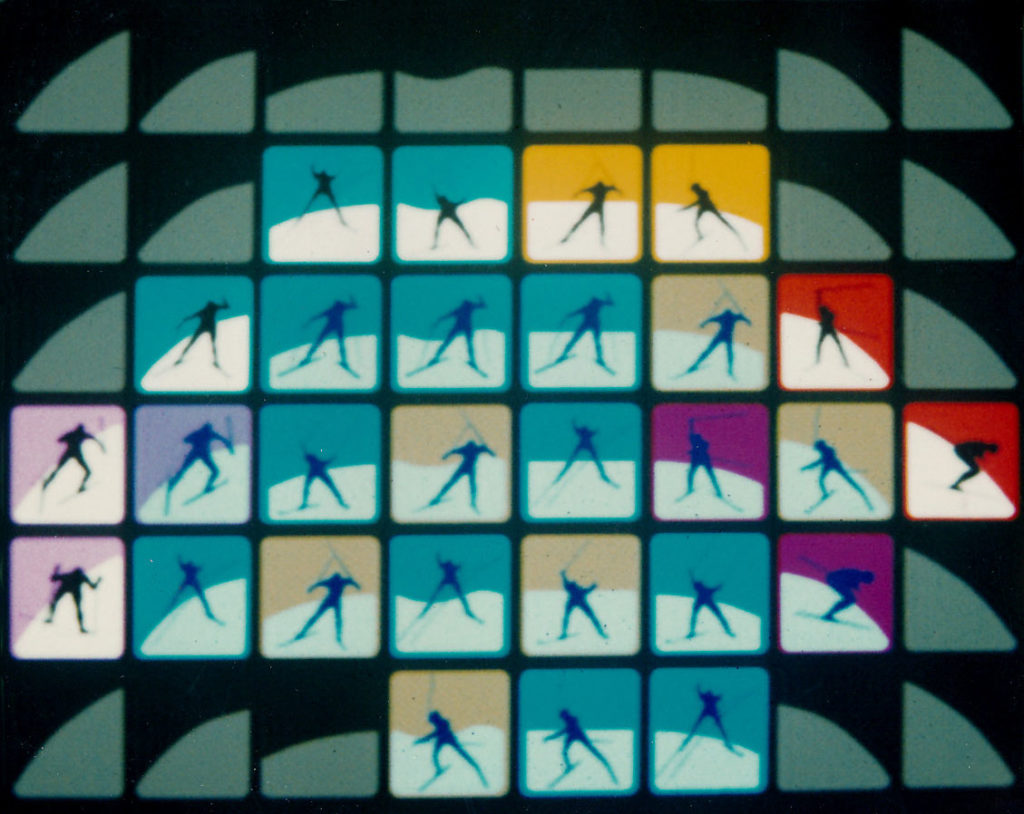

The first job I did for a paying client involved producing a series of graphic icons to be used on a video, Cross-country skiing for beginners with Bill Koch, directed and produced by Erich Lyttle. (Koch had won the silver medal in the 1976 Winter Olympics, becoming the first American to win an Olympic medal in cross-country skiing, and the only one until 2018.) The graphic icons were created with rendered 2D polygons so that they could be keyed over the video footage. It was a simple job but a huge milestone for me.

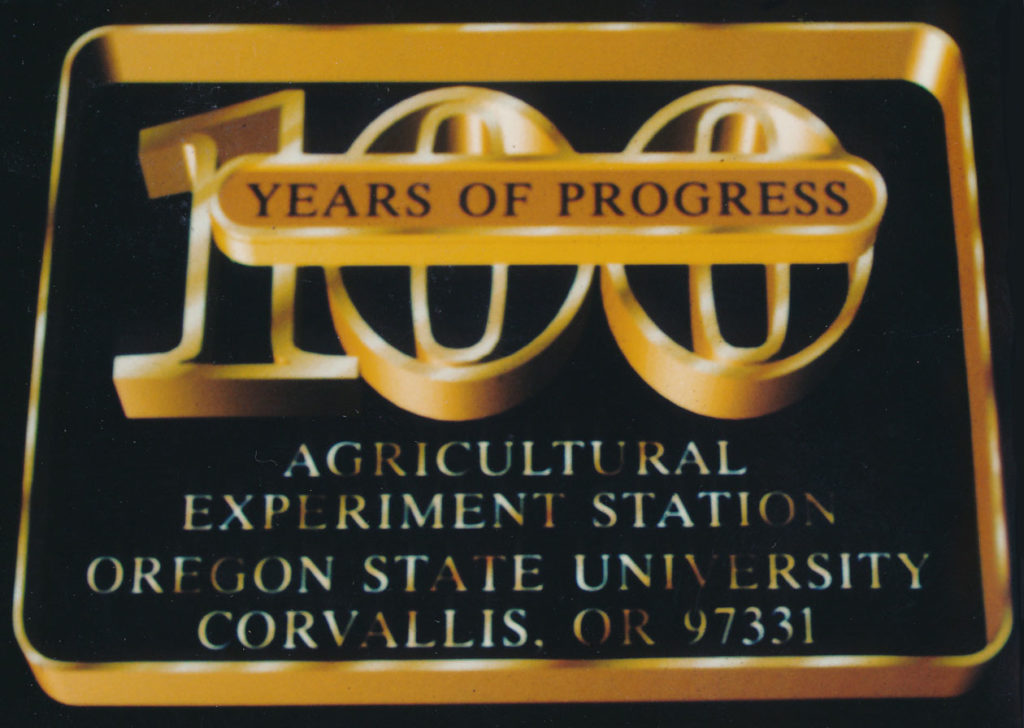

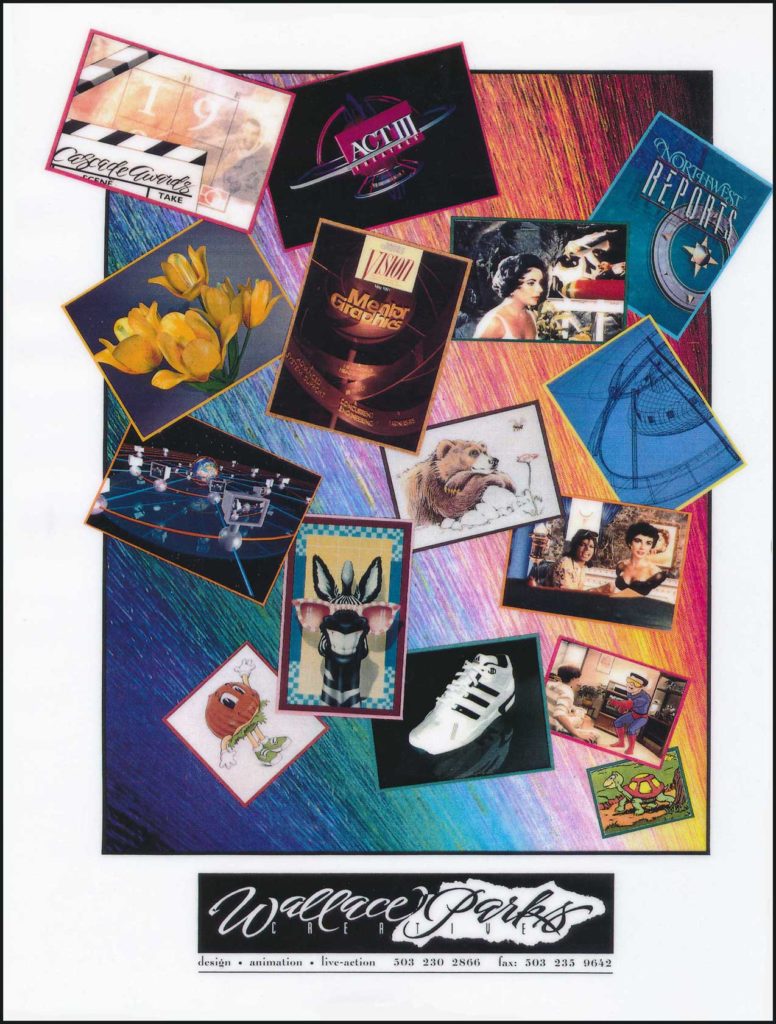

In the 1980s most of the commercial work available in 3D computer graphics consisted of “flying logos” that were broadcast on television for sports openings or television shows. Digital Artworks did a number of these for the New England Sports Network, the National Basketball Association, Major League Baseball, and a few NFL teams. Animator Paula Conn won an Academy Award for best animated opening for a TV series, As the World Turns. Other jobs included a famous spinning logo animation for MTV television that animator Erik Johnson produced, as well as numerous other 3D animations for commercial video production openings and transitions. We did several jobs for IBM, including an animation explaining superconductivity in a newly discovered ceramic material and an animation detailing a robotic hip replacement surgery that was years ahead of its time.

Our company was one of only a few boutique 3D animation production companies in the 1980s. We delivered commercial broadcast quality 3D animations for the bargain price of only $500 a second! At thirty rendered frames per second for video, that was pretty much a break-even deal for our company. We were always trying to get the big-time clients, so Digital Artworks kept its prices as low as possible, thinking that would attract local well-known clients like Nike and build a reputation as one of the go-to animation houses for the major broadcast clients. In hindsight, that was probably not the way to do it. Nevertheless, we kept getting jobs and Tom kept expanding the vision.

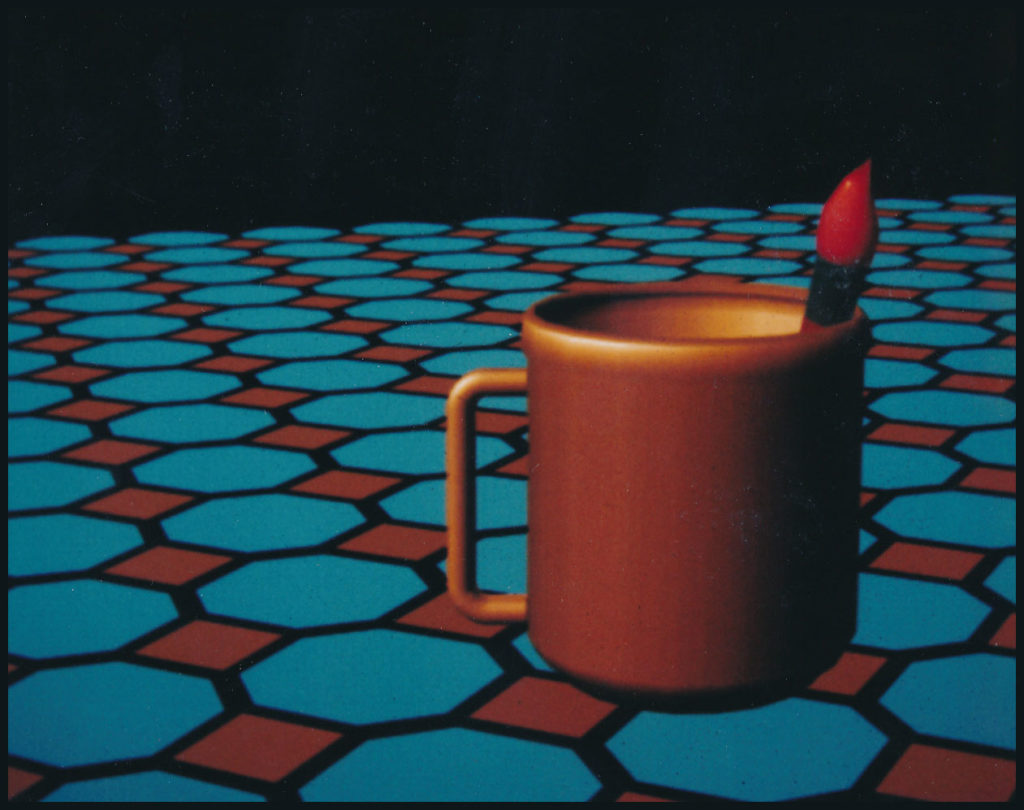

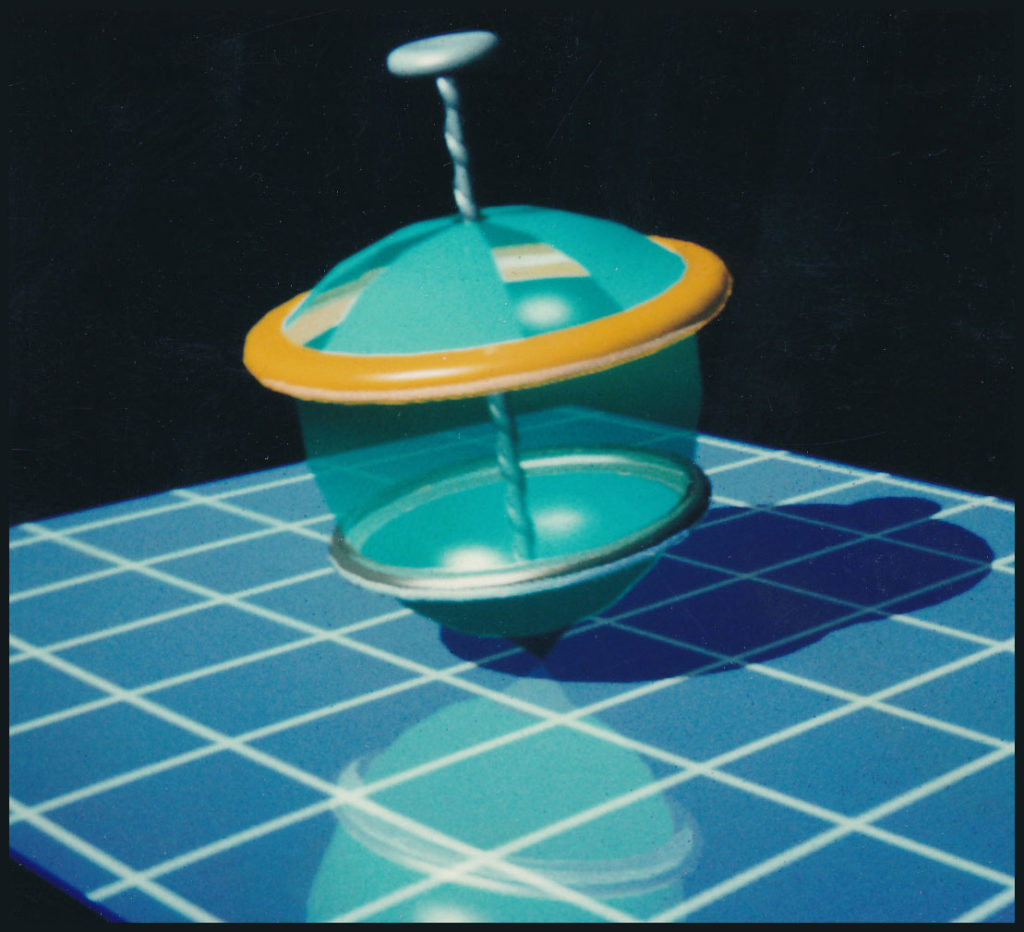

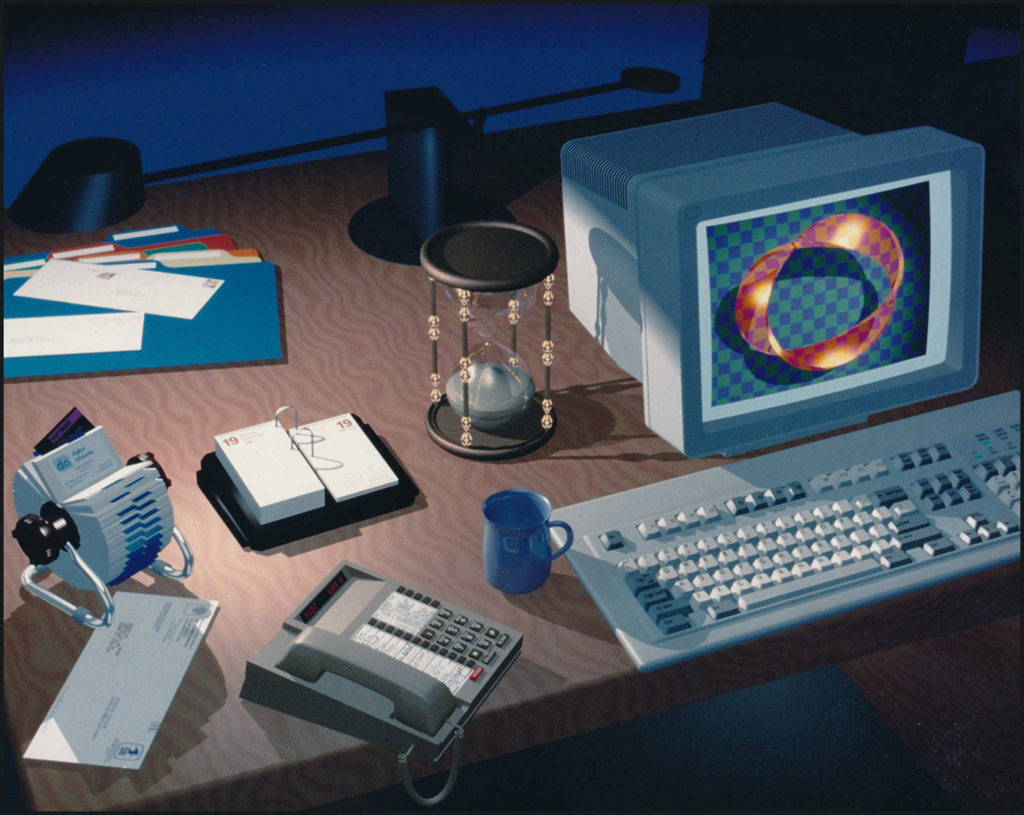

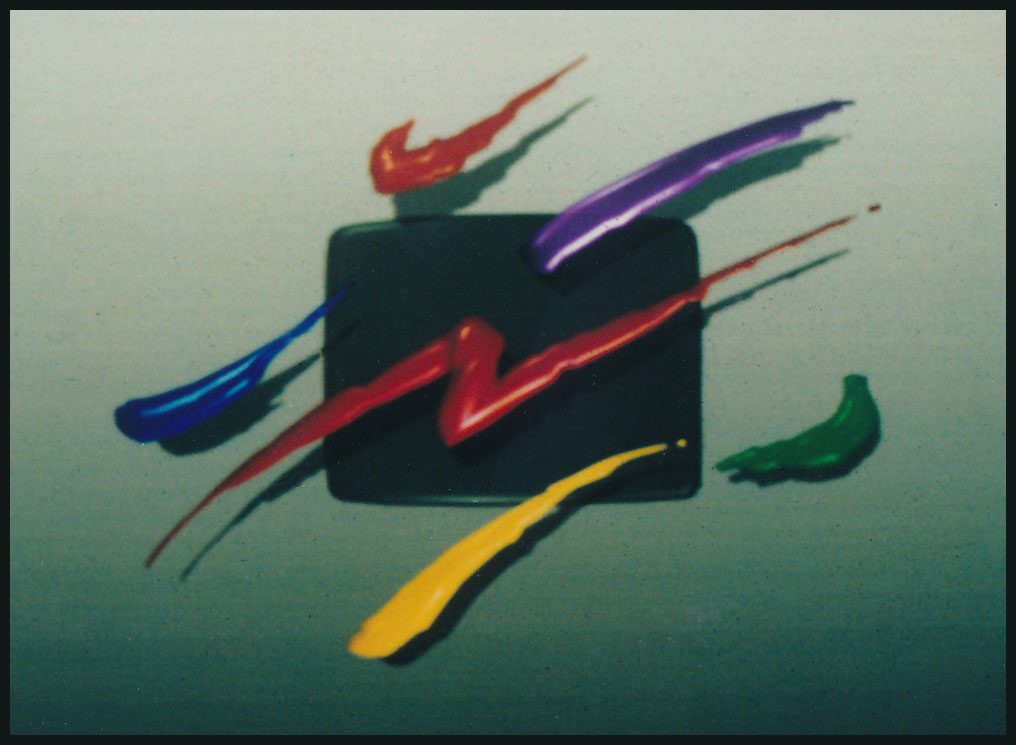

Individual frames could take hours to render, sometimes even days if ray tracing was used. There was no multi-tasking on PCs back then and only one process at a time could be running—completely tying up a workstation computer. Ray tracing was starting to become available for the Cubicomp around 1988 and that was a huge advancement. Basically, if you want to have calculated shadows, true reflections, or refraction in transparent objects in a scene, you need ray tracing. When we were finally able to incorporate a ray-traced environment in an animation it was fantastic. Although it usually took hours just for the computer to calculate one frame, it was mesmerizing to slowly watch an image grow with mathematically calculated reflections and shadows, scanline by scanline, as the computer rendering churned out on the RGB monitor.

It was an intense time and I usually worked six or seven days a week, but I loved what I was doing and the days seemed to fly by. Even though it did rain a lot in Eugene, especially when I first arrived, it didn’t bother me because I was spending my days in a warm, darkened room, building virtual worlds inside a high-resolution monitor. I was completely intrigued and absorbed with what I was doing.

A year or so after I moved to Eugene, Digital Artworks made a deal to expand our operations into a video post-production facility in Portland. Carl Johnson and I were sent there to operate a workstation and provide animation services for clients of this well-equipped video editing establishment. It was an important move for me and I was being trusted with representing Digital Artworks in the big city of Portland where there was a lot of high-end video and film work going on.

When I got an apartment in downtown Portland right across the street from my office at Northwest Videoworks, I felt like I was on top of the world. I was now a professional computer animator, working in one of the best post-production studios anywhere and doing projects with well-known producers for high-profile companies. I felt better about myself than I had in years and was very pleased with what I had accomplished professionally. I still carried the little brown amulet that Sister Rosa had given me a couple of years earlier and considered it a special good-luck charm that I should keep with me at all times. Everything had fallen into place for me since I drove west from her parlor in Santa Fe and even though I was not entirely committed to believing in charms or talismans, I nevertheless thought it best to do as she instructed.

Working at Northwest Videoworks in Portland was my introduction to the world of video post-production. When Carl and I were there we mostly serviced Portland video producers who were also using Videoworks to edit their projects. Having an in-house computer animation service was an added benefit to producers because they could do on-line editing and have an animated intro to their show done at the same time. A client could be in the master edit suite directing an editor cutting a project together and at the same time walk back to our office and direct how they wanted their 3D show open or transition. We could output our 3D visual effects work to a Betacam SP deck and walk down the hall to deliver the master to the machine room for the client who was in an edit session. All the while we were still employees of Digital Artworks; Tom had worked out a deal with the owner of Northwest Videoworks to combine efforts for the benefit of both companies.

The arrangement worked well and Tom expanded his vision yet again and made another similar deal with another major post-production house in Portland. Pace Video was Northwest Videoworks’ main competitor in Portland for video post-production and somehow Tom made a deal with the owner to set me up with an office and a workstation at Pace. I moved across town and began working there. I never did know how Tom was able to set me up at Pace and have Carl working at Northwest Videoworks. It didn’t matter much to me at the time because I was more than happy to be the only computer animator working at Pace.

Pace was a larger production house than Videoworks and had a Quantel Paintbox available to clients, as well as the new Digital Artworks 3D suite. The Quantel Paintbox was a dedicated computer graphics workstation for composition of broadcast television video and graphics. At a cost of about $150,000 per workstation, the Quantel was a highly priced addition to any video production facility at the time. The Quantel was one of the first digital visual effects compositing and paint systems for video.

Pace also had access to a couple of well-known Paintbox artists who were in demand by many producers. Now that 3D animation was also offered, we typically got projects with decent budgets that required a cutting-edge creative approach. The Quantel was in an adjacent office and we frequently combined artistic efforts to create unique content for producers. One project that stands out was a documentary for Frontline called “Anatomy of An Oil Spill,” produced by Boston WGBH-TV. I built a 3D model of the Exxon Valdez oil tanker and created a demonstration animation of how the ship collided with Bligh Reef in Alaska’s Prince William Sound in 1989. It was the worst oil spill in U.S. history until the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010. This probably was the first animation I did to be broadcast on national television.

By this time, I was getting a wide variety of experiences on a broad spectrum of projects. It was the end of the eighties and computer graphics technology had changed dramatically in the few years that I had been involved. Our company had abandoned the Cubicomp Picturemaker and advanced to purchase multiple SGI workstations running Softimage animation software. Softimage was a huge leap from Cubicomp. The software had an integrated 3D modeling, animation, and rendering package with a graphical interface that was targeted at visual artists. All of the animators working for Digital Artworks were delighted to have this revolutionary new animation software running on Silicon Graphics computers. We were one of the first 3D animation studios on the west coast to use Softimage and that proved to be a real stroke of luck for me because in the next few years the software quickly became the prevailing system for producing CG animation in feature films. I had a head start in learning Softimage, which set me up for my career in visual effects for the next decade.

While I was at Pace, I worked with a client who was a talented designer and animation enthusiast named Don Wallace. Don had done some amazing hand-drawn cell animation work and had also worked on an award-winning music video project for Michael Jackson with Portland artist and producer Jim Blashfield. Don was fascinated with the potentials of computer animation and we enjoyed collaborating and working together on a few video projects that Don brought to Pace. Around this time, the owner of Digital Artworks moved to Fairfield, Iowa, to pursue personal spiritual interests and jumpstart a new computer animation business. The animators in the home office in Eugene decided to consolidate and continue procuring animation work, but the relationship with Pace Video in Portland would close. I did not really care to move back to Eugene, so Don and I decided to combine our abilities and start a partnership business in Portland that would offer traditional cell and 3D computer animation, along with various illustration and visualization services.

The 1980s were about to come to a close and things were about to heat up really fast with Wallace/Parks Creative going into the ‘90s. My initiation was complete. I will forever be grateful to Tom Ravey for giving me the opportunity to come to Eugene in 1987 and apprentice with Carl, David, Paula, and Erik.

A few examples of very early computer animation. These projects appear extremely simplistic by today’s standards, however this is some of the very first commercial CGI work produced for broadcast television using commercially available software and hardware. This edit was made from thirty-year old VHS demo tapes that were recently transferred to digital format. The resolution is very low compared to most videos seen today. Although there are some glitches, the VHS tapes held up remarkably well over the years.

The ‘80s had seen the beginning of computer-generated imagery (CGI) for commercial use in television and film. Films such as Luxo Jr. (1986), the first CGI film nominated for an Academy Award, and Tin Toy (1988), the first computer-generated film to win an Oscar, set the stage for what was to come. In 1989, after James Cameron produced The Abyss and won an Academy Award for Best Visual Effects with the first digital 3D water effect, Hollywood was beginning to pay attention. In the early ‘90s, films like Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) and Jurassic Park (1993) would prove to be game-changers. But that’s the next decade, and a new chapter to the story.

Continued… ( If you would like to read the continuation of my story, “My life in visual effects and CGI during the 1990s” – please contact me for password. micheal@michealparks.com )